The glass age - begun with Pilkington's float process

The built environment in which we live today, with expansive glazed shop windows and construction epitomised by glittering glass high-rises like London's Shard, owes much of its existence to Sir Alistair Pilkington’s float process which made it far easier and cheaper to make high-quality glass.

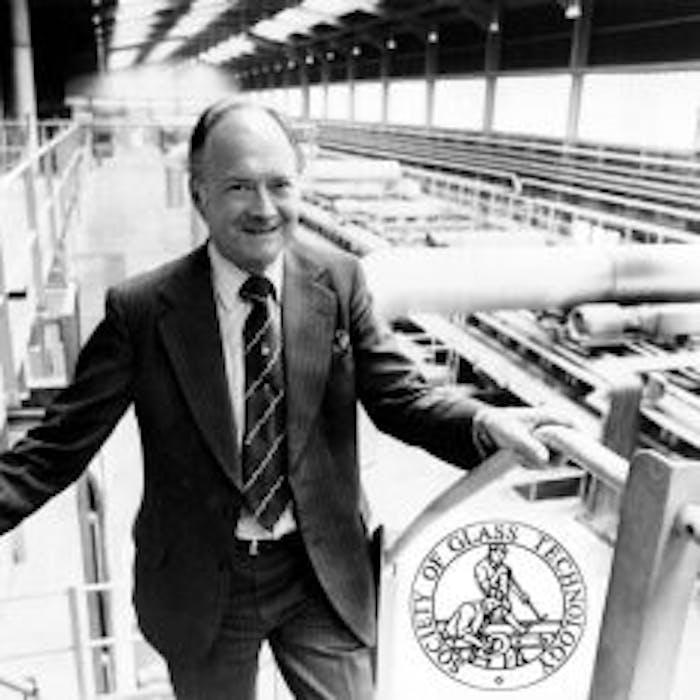

Sir Alastair (1920-1995) was a British engineer and businessman who, after the War, obtained an engineering degree, followed by a job within the major UK glass manufacturers Pilkington Brothers. Surprisingly, he was not related to the Pilkington family which had established and still controlled the business.

He was an innovator, and set to work on a new glass-making process, the target of which was to make, more economically, the high-quality glass essential for shop windows, cars, mirrors and other applications where distortion free glass was necessary. At that time this quality of glass could only be made by the costly and wasteful plate process, of which Pilkington Brothers had also been the innovator. Because there was glass-to-roller contact, surfaces were marked. They then had to be ground and polished to produce the parallel surfaces which bring optical perfection to the finished product.

Sheet glass - glass made by drawing it vertically in a ribbon from a furnace - was cheaper than polished plate glass because it was not ground or polished, but it was unacceptable for high-quality applications, where it could not replace polished plate. Many people in the glass industry had dreamed of combining the best features of both processes. They wanted to make glass with the brilliant surfaces of sheet glass and the flat and parallel surfaces of polished plate. Float glass proved to be the answer.

Pilkington had the idea for the float process in the early 1950s, but it took seven years of hard work to prove that he was right, and the cost of developing the process was high, particularly for the family-owned company at the time. It involves a continuous ribbon of glass moving out of the melting furnace and floating along the surface of a bath of molten tin. The ribbon is held at a high enough temperature over a long enough time for the irregularities to melt and for the surfaces to become flat and parallel because the surface of the molten tin is flat. The ribbon is then cooled down while still on the molten tin, until the surfaces are hard enough for it to be taken out of the bath without rollers marking the bottom surface. This produces a glass of uniform thickness and with bright, fire-polished surfaces without the need for grinding and polishing.

The first foreign licence went to the Pittsburgh Plate Glass Company in 1962, and this was quickly followed by manufacturers in Europe, Japan, Czechoslovakia, the Soviet Union and others in the USA. Today, around 260 float plants are in operation, under construction or planned worldwide. Pilkington operates 25 plants, and has an interest in a further nine.

Further reading

Links to external websites are not maintained by Bite Sized Britain. They are provided to give users access to additional information. Bite Sized Britain is not responsible for the content of these external websites.